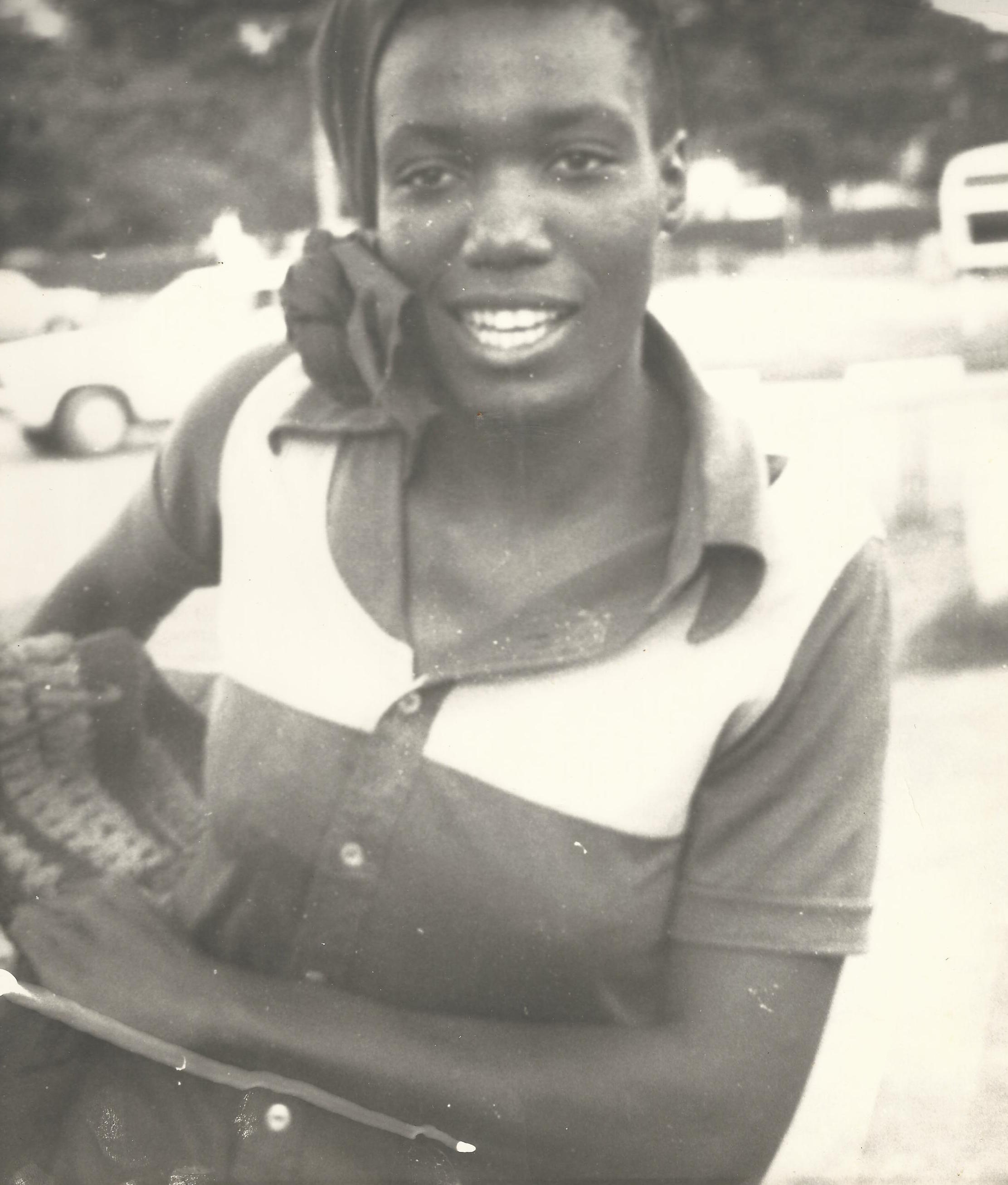

Lucy Banda Sichone Profile

Lucy Banda Sichone (Zambia & Somerville 1978) was a human rights activist and educator. In 1978, she was selected as Zambia’s first female Rhodes Scholar. She was admitted to Somerville College and read for a BA in Politics, Philosophy and Economics. Upon her return to Zambia, Sichone practiced as a lawyer and public defender, and founded the Zambia Civic Education Association. Notoriously outspoken, Sichone made a name for herself challenging and chastising her country’s government officials. She died in 1998. This profile was drawn from an interview with Lucy Banda’s daughter, Martha Sichone-Cameron.

Rhodes Project: Lucy Banda was one of the only women in her course at university. How did that shape her experience?

Martha Sichone-Cameron: She really took it in stride. Her parents had raised her to get an education in spite of the odds. When she was younger, they shaved her head just to make sure that she was able to make it through the earlier years of school, as it was still frowned upon for young girls to go to school. Because of this, she grew up like a tomboy until she was able to attend an all-girls secondary school run by Dominican nuns. Part of that played into her character. Mom wasn’t very feminine. She tried to be, but it wasn’t her. She was competitive and she could hold her own.

Rhodes Project: What was the reaction in Zambia when your mother was awarded the Rhodes Scholarship and became Zambia’s first female Rhodes Scholar?

Martha Sichone-Cameron: I was told that it was a very exciting time. Her parents were very proud, and it was talked about by the whole community that their daughter was going to England. In those days, public attitudes about Europe were still reminiscent of the colonial era. British and white people were held in high esteem. Very few people were travelling to the UK—only politicians and wealthy people—and now, a regular person from a “poor” community was going. So there was a huge send-off. I don’t mean a party—but when she was leaving the community, getting to the airport and getting on the plane, the whole community was there at the various points to see her off.

Rhodes Project: How would you describe her style of motherhood?

Martha Sichone-Cameron: She was not intimate (e.g. lovey-dovey, hugs and kisses) with us, but we never doubted her love. She got us everything that we needed. She never allowed me to go out to parties when I lived with her, let alone date anyone; I was never able to go out until I went to college. When she went shopping for me she always bought me the latest trends in clothes, but I could never wear them anywhere except church! A lot of times my friends would borrow them because they were able to go out. But there was a motherly side to her, and she tried her best to take care of us and show us that she loved us.

Rhodes Project: Did your mother ever get married?

Martha Sichone-Cameron: Eventually. One of the things that really surprises me now is that my mother and father were not engaged when they had me. This was still in a very traditional, conservative climate. In some of our family pictures, like when I got my first tricycle, you see both of my parents with my grandparents. In that day and age, that would have been unheard of - my dad wouldn’t have been interacting with my grandparents. Traditionally, first of all, my dad would have probably had to pay “damages” for making my mother pregnant. This happens still to this day. You can get away with just paying damages and child support if both people are of age, but in the old days, the man would have to take the girl as a wife, and would pay the dowry in addition. So my father must have made some sort of formal (traditional) approach to my grandparents. He must have acknowledged that he was the father of the baby, and acknowledged the fact that he was interested in marrying my mother. But they did not formally get married until 1979, when I was 5 years old. I believe this was prompted by the fact that she got the Rhodes Scholarship and would be away in the UK for some time. She would have also been pregnant with my brother at this time.

After my father died, my mother’s love life turned into a tragic love story. It took her 10 years before she attempted to get married a couple of times, and the second marriage was shrouded in controversy. I have two younger siblings from that time. Today, as I did at the time, I continue to defend my mother’s decision to get married when and to whom she did.

Rhodes Project: What inspired your mother's interest in fighting for education?

Martha Sichone-Cameron: Her father had been very strict about her education. At some point he had served as a butler for a British colonial family where he began to take a keen interest in getting his daughters educated. She went to an all-girls secondary school that was also a convent. She was vastly competitive, and of course she was brilliant. This became very apparent in secondary school when the German nuns pushed all of their girls to do well and go to college.

When my father died, my mum experienced something called ‘property grabbing.’ All our household goods were taken by my father’s relatives. Additionally, because we are a patrilineal society, the children technically belong to the man’s side of the family. My mother had legal training and she fought for actual legal custody for us; most women at the time would never have had that opportunity. We are lucky that she did that. My mother never let me forget that, right from the time I started school. The whole basis of making sure I got the best education, and her emphasis on doing well in school, came from her belief that “education means independence—it means that nobody can take advantage of you.” That used to be pummelled into my head. If I didn’t do well at school, she would say, “Do you want something like what happened to me to happen to you?”

Rhodes Project: What issues was she most passionate about and how did she encourage this passion in others?

Martha Sichone-Cameron: She represented so many clients over a wide range of issues, from government land disputes to personal issues similar to those she had experienced as a widow. She would tell people, “You need to wake up, and you need to understand what is going on.” People probably thought she had some kind of affiliation with the opposition political party because she would say, “You need to hold these people (in government) accountable, and you need to take (civic) responsibility” and “You need to vote for someone who is going to do this and not someone who is going to do that.” She was going around the country sharing these thoughts, spending many sleepless nights because of traveling. People wanted her to come and speak all over the country and she would get really tired. But I understood her work ethic and her need to get out there; when you went and saw how desperate people were, it was almost hard to believe you were living in the same country. I travelled with her a few times and saw exactly what she was dealing with. It was absolutely incredible and sometimes downright dangerous.

Rhodes Project: What was her main source of conflict with the Zambian women’s movement?

Martha Sichone-Cameron: She didn’t completely agree with the way the gender movement came about and was being propagated in Zambia. She didn’t agree with the way some of the women’s rights activists were promoting women’s rights. She thought that women’s rights were encompassed in human rights. She felt that they were misleading the Zambian people by making them become disrespectful to men and abandon some of their cultural norms. There were a lot of gender seminars and workshops and it became such a hot issue. My mother would speak contrary to that and say, “The same people who are holding all of these gender conferences and telling you to be disrespectful to your husbands will go back into their homes and take off their gender hats and play the traditional role of the woman. They’re lying to you. They have not stopped being women in their houses.” However, she believed that your gender did not take away your human rights. She wanted to encourage women to be better and to be treated equally in terms of professional choices both in government and in other places, she wanted girls to get their education, but she never wanted that to corrode some of the cultural and traditional values.

Rhodes Project: When you were young, your mother once went into hiding to resist being arrested by the Zambian government for writing an article that criticized a parliamentary decision. What were your daily lives like during this period?

Martha Sichone-Cameron: When she was a fugitive and “resisting arrest,” it was actually pretty anticlimactic. She was at home for the most part; she was not running around hiding. They knew exactly where she was too. We would not let people into our house; we had armed paramilitary guards. The only way they were going to get her was if they came in with a warrant for her arrest. The arrest was going to be for one of the articles that she had written in the leading private newspapers. They made an announcement that they were looking for her but then did nothing about it. As soon as they made that announcement that she was a wanted person with a reward attached to her head, there was international pressure from human rights groups, journalists and legal groups to absolve her because she had a three-month-old baby at that time. It wasn’t as dramatic as you would think; she ended up winning an International Women Media Foundation award for the same article for which they were trying to arrest her.

However, after a brief period of hiding at home, people started to tell her that this was really serious, that she had to leave her house and go somewhere else. We drove for four hours to my grandmother’s house. We must have gone through at least four or five police checkpoints. My mother was a public face and they had been told everywhere to look out for her, but when we passed through the checkpoints they would recognize her, chat with her a little bit and then let her go. That’s how much people respected her. They knew that she was helping a lot of people and that what the government was doing to her wasn’t fair. We knew that the threat was real and imminent, but at the same time, people treated her with respect and we saw that they weren’t going to let the government take her away.

Rhodes Project: How has her legacy affected you?

Martha Sichone-Cameron: I look back on her life and feel like I will never be as strong as her. I was closer to her in the last two years of her life, when her health was failing, than I had ever been. Even looking at the circumstances of our lives, I don’t think there was a time earlier on when we could have had as close a time as that. Early in our lives, she was in a position where she had a tough life and we had to get tough love. I wouldn’t be as educated, nor would I have pushed for my brothers and sister to get their education, if my mother hadn’t built my character the way she did. I wouldn’t have the life I have now. I am grateful for what she gave to me. I have to look at those things and say yes, she had a tough life, she was a single mother, and she felt that she had this vocation that she had to live out. My pursuit of education, my character and my vocation—which is to help women (mostly widows) affected and infected by HIV, as well as HIV orphans—is all because of my mother’s life and legacy.

I miss her dearly. Now that I am older and wiser, I wish I could let her know how much more I appreciate her life and legacy—a life that we had to share her with the whole country.

Back to Scholar Profiles A-E

© 2015